NF1 PN are prevalent, progressive, and debilitating1-3

PN are a common manifestation of NF1 that occur early and may progress over time1-3

PN are highly variable and have the potential to cause life-altering clinical complications.4

Up to

50%

of all patients with NF1 have PN2,3*

Results from the NCI NF1 Natural History study over 5.6 years showed5†:

82% of patients with NF1 PN

had tumor progression ≥20%

The median growth rate was

16% per year

(-3% to 136%)

In general, PN grew

continuously

*Using whole-body MRI. 3

†The NF1 Natural History study began in 2008 and is an ongoing study. Ninety-two patients with NF1-related PN between the ages of 3 and 18 years who had at least 2 volumetric scans were included in the analysis above as the age- and period-matched external control for the SPRINT study.6

MOA=mechanism of action; MRI=magnetic resonance imaging; NCI=National Cancer Institute; NF1=neurofibromatosis type 1; PN=plexiform neurofibromas.

NF1 PN: a growing concern

In patients with NF1 PN,

PN volume

growth rates

can exceed weight or

height growth rates7-9‡

In the NCI NF1 Natural History study,

PN typically continued to grow.6§

Percentage change in target PN volume, Natural History study6§

‡Based on 2 longitudinal studies, including 49 patients with 61 tumors and 70 patients with 80 tumors.7,8

§The NCI NF1 Natural History study began in 2008 and is

an ongoing study. 92 patients with NF1-related PN between the

ages of 3 and 18 years who had at

least 2 volumetric scans

were

included in the analysis above as the age- and period-matched

external control for the SPRINT study.6

PN typically grow fastest in the first 10 years of life.2 Early action is crucial.4

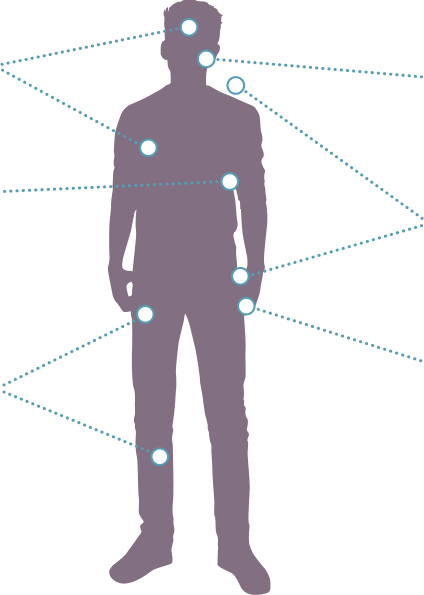

PN are a significant cause of morbidity in pediatric patients with NF11,2

Visible deformities throughout the body1

Airway compromise1,4

Motor dysfunction1,9

- Weakness

- Difficulty walking

- Numbness

Vision impairment10

PN-related pain throughout the body1

Bladder/bowel dysfunction1

PN are a significant cause of morbidity in pediatric patients with NF11,2

Vision impairment10

Visible deformities throughout the body1

Airway compromise1,4

PN-related pain throughout the body1

Bladder/bowel dysfunction1

Motor dysfunction1,4

- Weakness

- Difficulty walking

- Numbness

Some internal PN are seen only on MRI. Advanced imaging plays an

essential role in diagnosing and disease management.1,4

See advanced imaging of PN in a Koselugo patient here.

PN morbidities can worsen

over

time4

In a retrospective study of a French cohort of pediatric patients

with NF1 PN

(N=78)11:

99% of target PN

were associated with ≥1 morbidity

89% of patients

had ≥1 target PN-related morbidity during the 24-month follow-up period

The burden of NF1 PN can go beyond physical symptoms12

Data suggest that children and teens with NF1 PN have difficulty with12:

-

Anxiety

-

Stigma

-

Depressive symptoms

-

Well-being

-

Peer relationships

-

Psychological stress

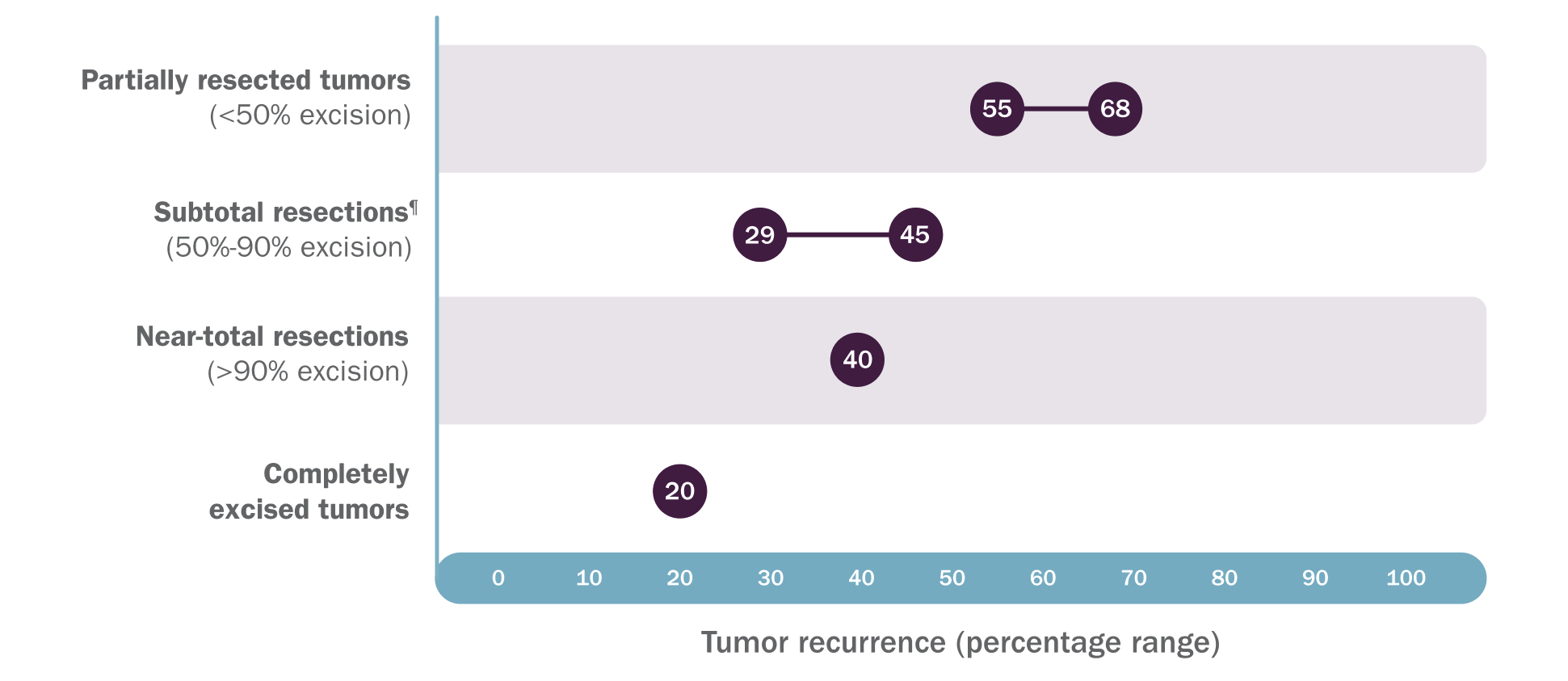

The surgical dilemma of NF1 PN

Not all PN require intervention, but when feasible, surgery is an effective means of resection and debulking13

PN regrowth is common after surgery and additional surgical challenges may occur.1,14,15

In 2 retrospective analyses, rates of PN regrowth after surgery range from 20%-68%, depending on extent of resection14,15||

‖Based on a review of inpatient and outpatient records of 121 patients who had 302 procedures on 168 tumors over a 20-year period at a single large pediatric referral center and a retrospective review of 96 patients who had 186 subtotal or partial resections on 130 tumors over a 10-year follow-up period at an NF center.14,15

¶In the 2012 study by Prada CE, Rangwala FA, Martin LJ, et al, subtotal resection was defined as 50%-80% excision.14

NF=neurofibromatosis.

Discover KOSELUGO® (selumetinib)

The FIRST FDA-approved therapy for pediatric patients with NF1 and symptomatic, inoperable PN.16,17

See study designFDA=Food and Drug Administration.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

Cardiomyopathy. A decrease in left

ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥10% below baseline occurred

in pediatric

patients who received Koselugo in SPRINT with some

experiencing decreased LVEF below the institutional lower limit of normal

(LLN), including one patient with Grade 3. All patients with decreased

LVEF were asymptomatic and identified during routine echocardiography.

The safety of Koselugo has not been established in patients with a history

of impaired LVEF or a baseline ejection fraction that is below the institutional

LLN. Assess ejection fraction by echocardiogram prior to initiating treatment,

every 3 months during the first year of treatment, every 6 months thereafter,

and as clinically indicated. Withhold, reduce dose, or permanently discontinue

Koselugo based on severity of adverse reaction. In patients who interrupt

Koselugo for decreased LVEF, obtain an echocardiogram or a cardiac MRI

every 3 to 6 weeks. Upon resolution of decreased LVEF, obtain an echocardiogram

or a cardiac MRI every 2 to 3 months.

Ocular Toxicity. Blurred vision,

photophobia, cataracts, and ocular hypertension

occurred. Retinal

pigment epithelial detachment (RPED) occurred in the pediatric population

during treatment with single agent Koselugo and resulted in permanent discontinuation.

Conduct ophthalmic assessments prior to initiating Koselugo, at regular

intervals during treatment, and for new or worsening visual changes. Permanently

discontinue Koselugo in patients with retinal vein occlusion (RVO). Withhold

Koselugo in patients with RPED, conduct ophthalmic assessments every 3

weeks until resolution, and resume Koselugo at a reduced dose.

Gastrointestinal Toxicity. Diarrhea

occurred, including Grade 3. Diarrhea resulting in permanent discontinuation,

dose interruption or dose reduction occurred. Advise patients to start

an anti-diarrheal agent (eg, loperamide) and to increase fluid intake immediately

after the first episode of diarrhea. Withhold, reduce dose, or permanently

discontinue Koselugo based on severity of adverse reaction.

Skin Toxicity. Rash occurred in 91% of 74 pediatric patients. The most frequent rashes included dermatitis acneiform (54%), maculopapular rash (39%), and eczema (28%). Grade 3 rash occurred, in addition to rash resulting in dose interruption or dose reduction. Monitor for severe skin rashes. Withhold, reduce dose, or permanently discontinue Koselugo based on severity of adverse reaction.

Increased Creatine Phosphokinase (CPK). Increased CPK occurred, including Grade 3 or 4 resulting in dose reduction. Increased CPK concurrent with myalgia occurred, including one patient who permanently discontinued Koselugo for myalgia. Obtain serum CPK prior to initiating Koselugo, periodically during treatment, and as clinically indicated. If increased CPK occurs, evaluate for rhabdomyolysis or other causes. Withhold, reduce dose, or permanently discontinue Koselugo based on severity of adverse reaction.

Increased Levels of Vitamin E and Risk of Bleeding. Koselugo capsules contain

vitamin E which can inhibit platelet

aggregation and antagonize vitamin K-dependent clotting factors. Supplemental

vitamin E is not recommended if daily vitamin E intake (including the amount

of vitamin E in Koselugo and supplement) will exceed the recommended or

safe limits due to increased risk of bleeding. An increased risk of bleeding

may occur in patients who are coadministered vitamin-K antagonists or anti-platelet

antagonists with Koselugo. Monitor for bleeding in these patients and increase

international normalized ratio (INR) in patients taking a vitamin-K antagonist.

Perform anticoagulant assessments more frequently and adjust the dose of

vitamin K antagonists or anti-platelet agents as appropriate.

Embryo-Fetal Toxicity. Based on

findings

from animal studies, Koselugo can cause fetal harm when

administered during pregnancy. In animal studies, administration of selumetinib

to mice during organogenesis caused reduced fetal weight, adverse structural

defects, and effects on embryo-fetal survival at approximate exposures

>5 times the human exposure at the clinical dose of 25 mg/m2 twice daily.

Advise patients of reproductive potential of the potential risk to a fetus

and to use effective contraception during treatment with Koselugo and for

1 week after the last dose.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Common adverse reactions ≥40% include vomiting, rash (all), abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, dry skin, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, pyrexia, acneiform rash, stomatitis, headache, paronychia, and pruritus.

DRUG INTERACTIONS

Effect of Other Drugs on Koselugo

Concomitant use of Koselugo with a strong or moderate CYP3A4 inducer decreased selumetinib plasma concentrations, which may reduce Koselugo efficacy. Avoid concomitant use with Koselugo.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Pregnancy & Lactation. Verify the

pregnancy status of patients of reproductive potential prior to

initiating Koselugo. Due to the potential for adverse reactions in a breastfed

child, advise patients not to breastfeed during treatment with Koselugo

and for 1 week after the last dose.

INDICATION

KOSELUGO is indicated for the treatment of pediatric patients 2 years of age and older with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) who have symptomatic, inoperable plexiform neurofibromas (PN).

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact AstraZeneca

1-800-236-9933

or at

https://us-aereporting.astrazeneca.com

or FDA at

1-800-FDA-1088 or

www.fda.gov/

medwatch.

Please see full Prescribing Information for Koselugo® (selumetinib).

References:

1. Korf BR, Rubenstein AE. Neurofibromatosis: A Handbook for Patients, Families, and Health Care Professionals. Thieme Medical Publishers; 2005.

2. Anderson JL, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1. In: Islam MP, Roach SE, eds. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 3rd series; vol 132. Elsevier B.V.; 2015:75-86.

3. Miller DT, Freedenberg D, Schorry E, et

al. Health supervision for children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5):e20190660. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-0660

4. Gross AM, Singh G, Akshintala S, et al. Association of plexiform neurofibroma volume changes and development of clinical morbidities in neurofibromatosis 1. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(12):1643-1651. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noy067

5. Data on File, REF-36656, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP.

6. Data on File, REF-75729, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP.

7. Dombi E, Ardern-Holmes SL, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, et al.

Recommendations for imaging tumor response in neurofibromatosis clinical trials.

Neurology. 2013;81(21)(suppl 1):S33-S40. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.

0000435744.57038

.af

8. Akshintala S, Baldwin A, Liewehr DJ, et

al. Longitudinal evaluation of peripheral nerve sheath tumors in

neurofibromatosis type 1: growth analysis of plexiform neurofibromas and

distinct nodular lesions. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(9):1368-1378.

doi:10.1093/neuonc/noaa053

9. Akshintala S, Baldwin A, Liewehr DJ, et

al. Longitudinal evaluation of peripheral nerve sheath tumors in

neurofibromatosis type 1: growth analysis of plexiform neurofibromas and

distinct nodular lesions (Supplementary). Neuro Oncol.

2020;22(9):1368-1378. doi:10.1093

/neuonc/noaa053

10. Avery RA, Katowitz JA, Fisher MJ, et al. Orbital/periorbital plexiform neurofibromas in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: multidisciplinary recommendations for care. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(1):123-132. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.09.020

11. Wolkenstein P, Chaix Y, Werle NE, et al. French cohort

of children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1 and symptomatic inoperable

plexiform neurofibromas: CASSIOPEA study. Eur J Med Genet.

2023;66(5):104734. doi:10.1016/

j.ejmg.2023.104734

12. Lai JS, Jensen SE, Charrow J, Listernick R. Patient reported

outcomes measurement information system and quality of life in neurological

disorders measurement system to evaluate quality of life for children and adolescents

with neurofibromatosis type 1 associated plexiform neurofibroma. J Pediatr. 2019;206:190-196. doi:10.1016/

j.jpeds.2018.10.019

13. Armstrong AE, Belzberg AJ, Crawford JR, Hirbe AC, Wang

ZJ. Treatment decisions and the use of MEK inhibitors for children with neurofibromatosis

type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. BMC Cancer.

2023;23(1):553. doi:10.1186/

s12885-023-10996-y

14. Prada CE, Rangwala FA, Martin LJ, et al. Pediatric plexiform

neurofibromas: impact on morbidity and mortality in neurofibromatosis type

1. J Pediatr. 2012;160(3):461-467. doi:10.1016/

j.jpeds.2011.08.051

15. Needle MN, Cnaan A, Dattilo J, et al. Prognostic signs

in the surgical management of plexiform neurofibroma: the Children's Hospital

of Philadelphia experience, 1974-1994. J Pediatr.

1997;131(5):678-682. doi:10.1016/

s0022-3476(97)70092-1

16. Koselugo. Package insert. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP.

17. Koselugo (selumetinib) approved in US for paediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 plexiform neurofibromas. AstraZeneca. April 13, 2020. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2020/koselugo-selumetinib-approved-in-us-for-paediatric-patients-with-neurofibromatosis-type-1-plexiform-neurofibromas.html#